The last several months tell a pretty solid story

/Hey there reader,

So it’s been a while since you’ve heard from us. About nine months ago Tessa and I founded Return Recycling to drive University communities across the country toward Zero Waste, and ever since we’ve been on an journey of epic proportions. Participating in business competitions, applying for research grant money, working with designers in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, digging through trash… really there are so many things that we’ve done it’s almost embarrassing that we haven’t written sooner. Neither of us realized how much we had launched ourselves into when we started this business. We’ve been strapped. In a good way.

In keeping with the values of the organization we’re trying to build though, we think that you deserve to hear it all. The good, the bad, and the ugly. So… if you can muster your way through this lengthy blog post, the following is a summary of where we’ve come from and what we’ve been up to. Aspiring toward transparency, community, and responsibility.

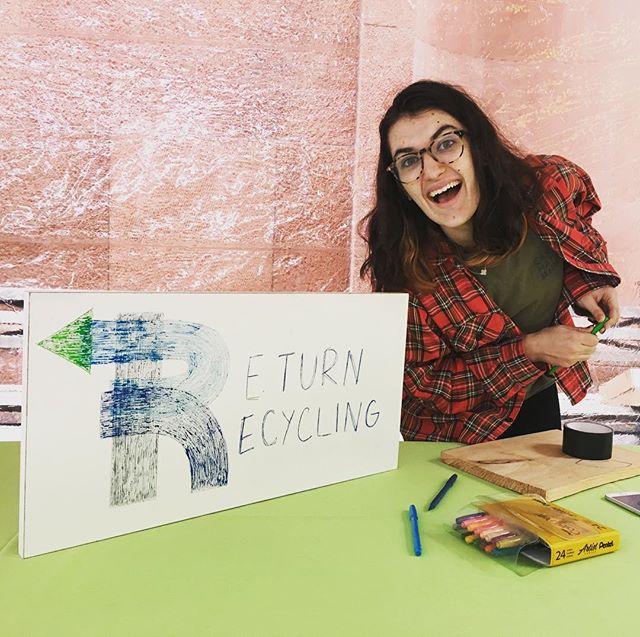

The seeds for Return Recycling were planted in the fall of 2013 after Tessa and I met at one of NYU’s oldest environmental organization meetings. The leader of the club, David Krantz, had asked everyone in the room to brainstorm different issues within environmentalism that we thought the university could better address and Tessa and I had gravitated toward the “waste management” discussion. Within days after, we started working together on a “recycling education program” that helped teach residents of NYU dorms how to recycle by tabling in their lobbies. We helped hundreds of students learn the basics of recycling at the school. And we loved it. And then Tessa went abroad. And things somewhat stalled.

Largely because of the work I’d done with Tessa during our sophomore year, I was hired as a Recycling Coordinator by the school’s Office of Sustainability to help raise the school’s recycling rates. Over the next several months I met many of the administrators within NYU responsible for guiding the school’s waste management protocols and witnessed first-hand the different issues that the university experienced regarding waste. According to these administrators, the waste that we disposed of as an institution, roughly 10 tons of recycling and trash, was mixed up so badly by students that it was difficult to tell what was recyclable and what was ultimately destined for landfill once it hit the curb. The administrators hoped that by establishing a consistent signage across the university, more people would understand how to recycle properly. So they made me responsible for locating existing problems in NYU buildings and making sure that our signage was consistent from building to building.

On my quest through NYU’s buildings, I quickly started to understand that recycling was particularly challenging for a number of different reasons. In some cases it was just that there were no recycling bins for students to use. So instead, they put everything they wanted to throw out in a trash shoot. These were simply infrastructural problems. So we fixed them.

Other times it was evident that students didn’t know how or what to recycle. When I was hovering near a recycling bin while on the job, I was asked countless times whether or not a wrapper could be recycled. So I gave small lectures to people that wanted/needed to know more and went from there. I’m did my best to make a lasting impression. Without sounding self-righteous and eco-preachy. Which was better than saying nothing.

Because in most cases I was simply haunted by the indifference with which some (if not most) of the students around me treated recycling. I watched thousands of people throw out aluminum foil when there was a perfectly functional recycling bin next to it and it made me question the worth of my job in the first place. Maybe I'm a bit neurotic, but I felt like I was going crazy. Why was I putting up signs if no one was going to read them?

So I thought about how the whole process might work better. How do you fight infrastructural, educational, and social issues within waste management in order to make progress toward zero waste? And at the beginning of our junior year I reached out to Tessa and again.

“Tessa, so you know all of the work that we were doing on recycling last year? Well, I want to design a better recycling bin for university spaces so that people will be able to engage with waste more intimately than they’ve ever been able to before. We’ll collect data on the trash, we’ll create economic projections based on the data we generate, and we’ll put advertisements on the bins we create in order to pay for the whole thing. And we’ll have this super cool space in Brooklyn where we sort through all of the trash and make art out of it and stuff… Wanna help me out?”

She said yes, but I was light years ahead of myself in the job description. I was under the illusion that everything was going to happen… in that very instant. Within a month after the start of school, I’d entered us into a business competition, applied for a grant, and already started to build out the team with a designer-friend from one of my classes and two other kids I’d met through a professor. There were three others besides Tessa and myself. I was incredibly hotheaded and irrationally prepared to dive the team into mass production of bamboo recycling bins. In retrospect, I might have pushed everyone a bit too hard those first weeks. It just seemed so necessary to drive hard into the start of the organization. That was how it started anyway.

After placing as semi-finalists in the Reynold’s Changemaker Challenge, we were awarded a Green Grant by the Office of Sustainability for nearly $10,000 to start prototyping our bin production and $610 by the Deans Undergraduate Research Fund for research purposes. I was so excited that I created a step-by-step list of tasks that needed to be accomplished in the next year for every person on the team. This was about three days before Christmas. And afterwards I never heard back from the designer I’d brought on to the team. Not a single email. I thought he’d died. And I’m still not sure what happened to him.

The timeline that I had created for our startup sort of smoldered to bits after the designer left the team. I went back to the drawing board, literally, and taught myself the basics of 3D modeling. I spent endless hours futzing with Rhino and creating dxl files that I eventually planned on sending to a CNC router for cutting. I couldn’t have done it without the help of Dustin Foster, a graduate student overseeing the 3D lab in the art building, or Jeffrey Taras at Associated Fabrication. They both answered some of my rather stupid questions.

During this time or somewhat afterwards, Tessa went to work on the website. Her minimalist framework drew heavily from our commitment to transparency. And… she nailed it. Half-way through the design phase of our bin we were able to start sharing our page with friends. It really helped to push our project forward.

While Tessa was hard at work on the website, I was simultaneously trying to find a place where we could actually assemble the bins. We’d originally hoped that the art building at NYU would allow us to share construction space, but due to overcrowding we were forced to look for other options. So I sent an email to an architecture professor, Mitchell Joachim, pleading for a corner of space in his shared working office at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He graciously answered. It couldn’t have been a better place to work. His design firm, Terreform One (check it out it’s incredible) was building chairs out of mold while we were there. It was inspiring energy to be around. Mitchell’s words of advice on how to build further designs of our bin still echo in my head.

By the time we actually got to the Navy Yard to start building our bins though, our project was about a month and a half behind schedule. And building the bins took us far longer than we originally expected as well. Tessa, Justin, Sebastian and I spent several nights up until 1 or 2 in the morning during the week putting the bins together when we could. Trying to balance our own commitments to school became really difficult. I spent so much time at the Navy Yard that I came very close to failing my math classes for Economics. I know Tessa was in the same place with her Linguistics class. (I could spend pages explaining the construction process of our bins… but I’ll save that for another time. I’m constantly trying to rethink the project. We could have done a lot of the work differently and made much better bins.)

Anyway, after many of those long afternoons and evenings at the Navy Yard we finally finished the prototype of our bins and brought them across the river in a Uhaul van to NYU. With help from the wonderful Christina Ciambriello, we’d secured three locations for the prototype bins in the Silver Academic Lounges at the College of Arts and Sciences. I don’t know where we’d be without her help on this project. When the bins arrived she did more than her fair share to make sure that they were well taken care of.

Because when our bins finally did arrive, they were a mess. They leaked liquid all over the lounges and they were much more difficult to clean than the stainless steel bins that they replaced. For the following two weeks after we introduced the bins into the lounge spaces we were doing repairs on them. I bought a cordless drill as a birthday present for myself because there was so much work that we needed to do on them. And so we learned. And then our research project began.

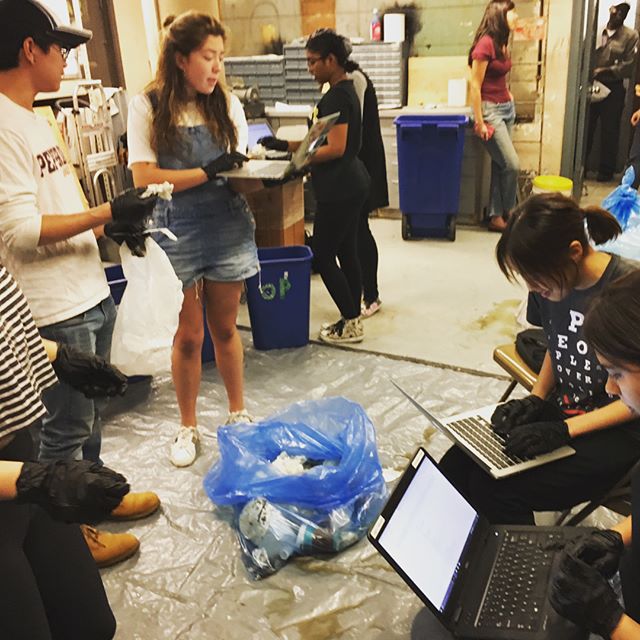

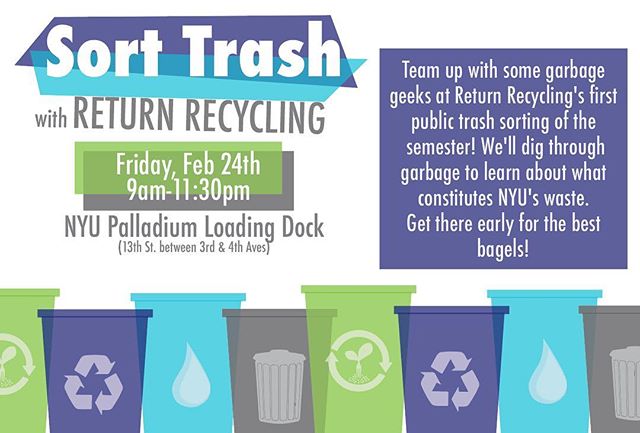

With help from some of the building cleaners (Janitors that deserve more than just a name drop here because of their patience and understanding) we were able to collect and sort about 150 lbs of trash that went through the bins we put into the space. On Tuesday mornings at 9am we would go to a garage on campus and dump the contents of the bags onto an open floor so that we could look through them. It was so much fun—and so time consuming—that I thought for sure Tessa and I would fail our classes. We stopped sorting trash about a week before the end of school so that we could all pass our exams… and so that the two other members of the crew, Sebastian and Justin, could graduate on time.

It all rushed by in a blur. Sooner than we could really process the whole semester, I left New York to visit my father in Alaska, Tessa went off to work for the National Park Service in Cape Cod, and Justin and Sebastian started searching for long-term jobs that would provide them them more security than our bamboo plexiglass experiment was capable of offering. It’s been difficult for our team to stay energized. We’ll be completely honest there. As students trying to make our footing in the world after college, we have so many different priorities that it’s incredibly difficult to commit to digging through the trash.

We’ve been at a point of reflection. Ultimately, we know that there is an enormous amount of value in the work that we’ve accomplished over the past year. It helps for me (and perhaps you too) to put some of the bigger points in bullets:

We’ve collected a wealth of data on trash in public spaces. The research study that we are in the midst of finishing (and publishing results to this blog), has shown just how effective the strategies we’re employing have actually been at reducing waste and increasing recycling rates.

We created a better recycling bin. It isn’t perfect, but by starting the design process we’re so much closer to developing a product that will knock people’s socks off.

We’ve made meaningful connections in the waste network and established ourselves as a meaningful presence at the school. Something that we can only hope to build off of when the fall semester starts again.

Now. The adventure continues. In the coming months you’ll hear more from us and we hope that it won’t be as overwhelming as an entire years-worth of activities and foundation building. We’re looking forward to our research release (!), discussing incorporation and fundraising, better bin development (the how and how should we), and all of the wonderful books that are sitting beside our beds. We’ll put thoughts and feelings and creative energy into this space so that you can better understand just how we’re tackling issues that plague us.

Much love and tenderness,

Davis